The apologists of capitalism are endeavoring to convince public opinion that a reduction in wages is an inevitable consequence of the economic crisis, for overcoming which further privations are needed "in the interests of the country", as if the crisis were something inexplicable, alien to these production relations and without class connotations. This statement is very far from the truth.

Before anything else, we must stress that the crisis is not simply “the crisis of economy” with no specification, but it is the crisis of capitalistic economy, originated by capitalism contradictions and endemic in capitalistic relations of production. Moreover, in this scenario, talking about "the interests of the country" is incorrect and false, since the country is divided into antagonistic classes, which do not have and can not have common interests.

Due to the very nature of capitalistic relations of production (the inverse proportionality between wage and profit), capitalists have always been trying to compress wages, but as long as the USSR has existed, in order to prevent the radicalization of the working class’ struggle, capitalists were obliged to grant higher wages, benefits and welfare. Cold War has been the golden age of social democracy and its social compromise. Since the USSR disappeared, capitalists have completely restored their political power to impose profit as the only independent economic variable with no downward flexibility. Labor remunerations in all their forms, direct (wages), deferred (pensions), or indirect (social services), any other distribution of surplus value may be put into question, reduced and cut, excluding profit. The generalized competition among monopolies, imperialistic countries and blocks strengthened this trend and put an end to traditional social democratic policies of compromise and social peace.

An example of the above is provided by the acceleration of the European integration process after 1991. In Italy, this process and, above all, the entry into the system of euro as the single European currency, was carried out by reducing wages and imposing burdensome economic sacrifices on the working class and the other people’s layers. At that time, left-centrist governments were striving to present sacrifices as temporarily necessary for the sake of a bright future in a united Europe. History unveiled their lies. Since its very beginning integrated Europe has shown its true face of imperialistic conglomerate, an enemy to workers and peoples, aimed at intensifying the exploitation and the robbery on waged labor. Nothing positive came from the European integration process to the working class, but the constant worsening of their living conditions, well before the outbreak of the crisis.

In particular, in Italy the introduction of euro was implemented in a fraudulent way, by rigging the National accounts in order to formally meet Maastricht parameters while Italian economy was far from them. The loss of the possibility to use devaluation to increase competitiveness due to the fixed exchange rate (1 euro = 1,927.36 lira), the anti-inflationary policy of budgetary rigor that hit pensions and social services, and the weakening of class struggle by reformist labor unions, supporting the anti-workers measures carried out by left-centrist governments, have jointly dragged down wages before the outbreak of the crisis. Moreover, many prices were adjusted to euro at the rate of 1 to 1000, with no intervention by governments and prices supervisory bodies. The wages decrease caused a depression of the domestic demand that finally hit those sub-sectors that had most taken an unfair advantage from the conversion of prices from lira into euro (commerce, restaurants, bars and catering, etc.), dragging a part of the bourgeoisie too into the gorge of the crisis, but the net result of these processes has been a huge transfer of wealth from the people to big capital.

The last crisis has undoubtedly contributed to worsening the living conditions of workers, but it is not the first cause of wages decrease in the long run. Wage reduction is an unavoidable tendency under capitalistic relations of production, as Karl Marx taught us. Here we should synthetically recall the distinction by Marx between nominal (monetary) wage, real wage and proportional wage. The nominal wage is the amount of money the worker receives, the formal price of the labor power. The real wage is the amount of goods and services the worker can buy with his nominal wage. The proportional wage is considered in relation to profit, both being two of the components of the distribution of the surplus-value produced, and measures the dynamics of the worker’s social position. Wage, being the price of the labor power, is determined by and connected to the value of it, that means to the amount of goods, services and spiritual values socially and historically needed for the re-production of the labor power. This value changes with the economic, cultural, scientific and technological development of society with an increasing trend. Just as an example: before smartphones appeared on the market, nobody felt the need of them, but after they soon became necessary to everybody. Prices never exactly reflect the values they originate from, due to the relation between supply and demand, principally, and other market conditions, secondarily. As the result of the production process restructuring (reorganization of the division of labor) and the technological replacement of labor power with machinery, labor supply generally exceeds labor demand and this objectively determines the permanent tendency to wage reduction under capitalism. This is one of the main contradictions of the capitalistic labor market: the labor power value historically grows, but the price of labor power (wage) tends to fall towards its physiological limit and, in some cases, even lower. Real wage depends not only on the amount of nominal wage, but also on many other variables, such as prices level and inflation, taxation, level of unemployment, everything can affect the relation between labor supply and demand. Even in the event if nominal wage rises, real wage may decrease by effect of price or taxation increase, or monetary devaluation, if their growth is more than proportional to the increase of nominal wage. As said before, proportional wage is a part of the distribution of the surplus value produced, along with profit. Given a certain amount of surplus value, if profit increases, wage automatically decreases. From this inverse proportionality of wage and profit the irremediable conflict objectively arises between labor and capital. On the one hand, in particularly favorable market conditions, an increase in both nominal and real wages may occur, but "... proportional wages may decrease even if the real wage rises together with the nominal wage, that is, together with the monetary value of labor, provided that it does not rise in the same proportion as the profit. If, as an example, in times of good business the wage increases by 5% while the profit increases by 30%, the proportional, relative wage has not increased, but decreased..."[8] On the other hand, it is a matter of fact that capitalism constantly improves labor productivity and intensity by applying new labor-saving technologies and forms of division of labor that allow to reduce the necessary labor time, needed to produce livelihood for the labor power reproduction, and expands the surplus labor time, from which surplus value and profit originate. Due to this, an objective tendency exists of the proportional wage to fall. Generally, even in those rare and short periods, when the real wage and the material living conditions of workers improve, this "...does not eliminate the contrast between the interests of the worker and the interests of the capitalist...",[9] because proportional wage has anyway decreased and the social gap with respect to capitalists has grown.

While capitalistic profit is firmly protected by the political power of the bourgeoisie, social disparities and the gap between the rich and the poor are increasing in Italy. Inflation is being artificially stimulated by the ECB and contributes to aggravating this situation, reducing the real wage, ie the purchasing power of workers. Moreover, provided the inverse proportionality between wages and rate of unemployment, the current high level of the latter causes an excess of labor supply over labor demand, that is generally structural, but is emphasized in crisis situations.

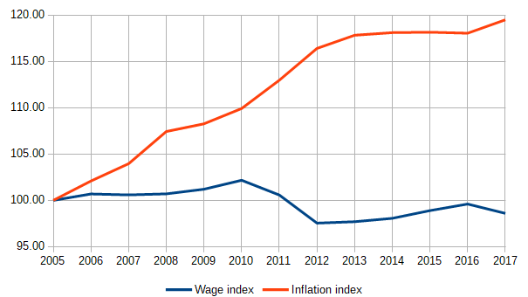

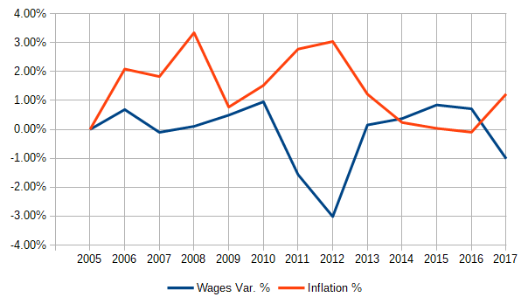

The above is confirmed by Tab. 3.1, based on OECD data, where average annual gross nominal wages, their index W and inflation (both in percentage yearly variation and index) are considered.

Tab. 3.1 – Average annual gross nominal wages (index and yearly variation) and Inflation (2005-2017)

|

|

Annual Average Wages

constant prices € 2017

|

W

|

Inflation

|

|

index 2005=100

|

%

|

%

|

index 2005=100

|

|

2005

|

29,630.33

|

100.00

|

0.00%

|

1.99%

|

100.00

|

|

2006

|

29,834.76

|

100.69

|

0.69%

|

2.09%

|

102.09

|

|

2007

|

29,805.48

|

100.59

|

-0.10%

|

1.83%

|

103.96

|

|

2008

|

29,837.94

|

100.70

|

0.11%

|

3.35%

|

107.44

|

|

2009

|

29,985.41

|

101.20

|

0.49%

|

0.77%

|

108.27

|

|

2010

|

30,272.54

|

102.17

|

0.96%

|

1.53%

|

109.92

|

|

2011

|

29,800.04

|

100.57

|

-1.56%

|

2.78%

|

112.98

|

|

2012

|

28,902.03

|

97.54

|

-3.01%

|

3.04%

|

116.42

|

|

2013

|

28,946.86

|

97.69

|

0.16%

|

1.22%

|

117.84

|

|

2014

|

29,055.92

|

98.06

|

0.38%

|

0.24%

|

118.12

|

|

2015

|

29,302.24

|

98.89

|

0.85%

|

0.04%

|

118.17

|

|

2016

|

29,512.07

|

99.60

|

0.72%

|

-0.09%

|

118.06

|

|

2017

|

29,213.56

|

98.59

|

-1.01%

|

1.23%

|

119.50

|

|

Source: OECD data, our elaboration

|

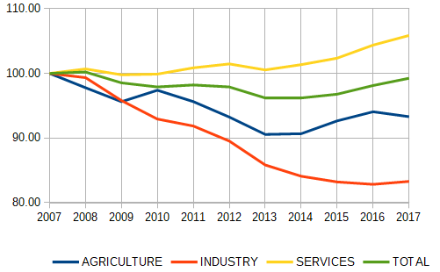

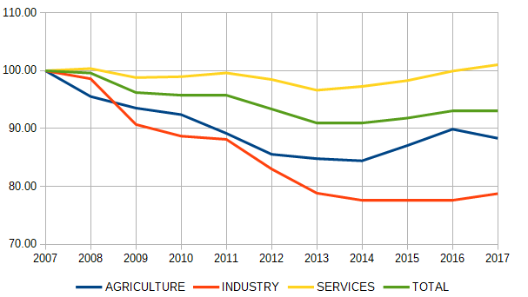

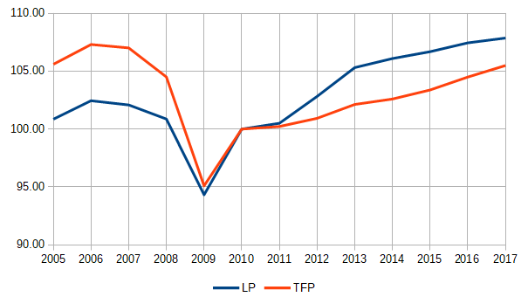

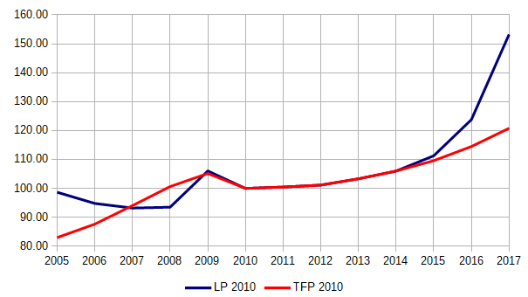

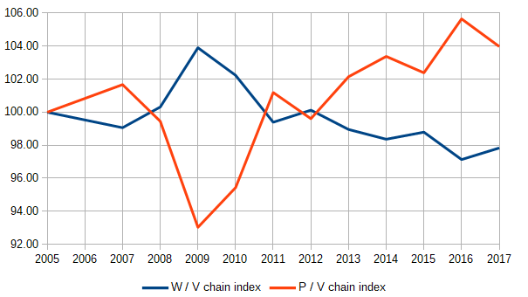

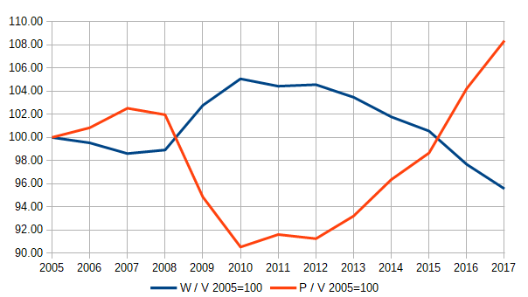

The wages' decrease is immediately evident even if we consider just nominal gross wages,[10] that fell by -1.41% compared to 2005 and by -3.5% compared to 2010. Despite the alarmist declarations of the ECB and the employers' organizations, actual deflation is in fact limited to 2016, with a price variation by only -0.10%. In all the other years considered, on the contrary, there is an average increase in prices by +1.54%, even if their annual variation is sometimes so weak as to confirm a depressive phase. For the purposes of our analysis, however, it is important to point out that the yearly variation of wages remains quite always below inflation, measured as the yearly variation of the consumer price index, except in 2014, 2015 and 2016.

If these are the dynamics of gross nominal wages, it is easy to guess, even without the need for graphs and tables, that the dynamics of real wages are far worse, if we consider:

- the fiscal burden: tax rates on personal income and the income brackets for their progressingtaxation have been amended several times, but always in the name of reducing the tax burden on higher incomes; after the fiscal reform of 1974 we had 32 income brackets, the highest tax rate for incomes higher than 500 millions lira was 72%, the lowest was 10%; in 2018 we have 5 income brackets, the highest rate for incomes over 75,000 EUR is 43% (only on the part of income exceeding 75,000 EUR), the lowest is 23%; the tendency is to eliminate the concept of progressing taxation; it is no coincidence that the government Northern League - 5 Star Movement, representing a strongly export-oriented section of industrial capital, are trying to introduce the so-called flat tax, which has an incidence proportionally higher on lower incomes. Currently, if we take an average gross wage of 29,213.56 EUR (see Tab. 3.1), the incidence of direct taxation and social charges, paid by workers, is equal to 39% of it. Therefore, the wage net after taxes amounts to 17,820.27 EUR. However, what most strikes the workers and contradicts the principle of progressing taxation established by the Constitution is indirect taxes (VAT not deductible for final consumers, excises and duties on which VAT is often applied with multiplier effects of the final price, etc.), as they tax consumption regardless of income and mainly damages workers, obliged to spend the majority of their income for consumption of essential goods. During the period we are considering for our analysis, the VAT rate has increased from 20% to 21% in 2011 and to 22% in 2013, excises on alcohol, tobacco, gasoline and oil derivatives have increased almost once a year; stamp duty and registration duty have also increased, together with other various local levies;

- the cut and privatization of public basic services, from healthcare to education and transport: they became chargeable and their prices increased;

- wage indexation is not calculated on the basis of actual inflation, but on the one programmed using the known accounting tricks.

Considering the above, it is not difficult to understand that real wages decreased much more than nominal ones. Wage and inflation dynamics are shown in Chart 3.2 (long term variation) and Chart 3.3 (yearly variation).

Chart 3.2 – Average wage index and Inflation index